Impact Night!

October 8, 2009

The moment of truth has almost arrived for LCROSS. At 4:31 AM Pacific time, 7:31 AM Eastern time, the spacecraft is scheduled to slam into the moon at more than 2600 miles per hour, raising a plume of debris more than 6 miles up into the lunar sky. (I was about to write “into the air” there for a second, but of course that’s wrong because there is no air on the moon! In fact, the correct phrasing would be “into the lunar exosphere,” but then you might not know what I was talking about.) As I write this, LCROSS is about 42,000 miles and 17 hours of flight time away from its target.

Of course, all the information that you could want is at the LCROSS website, including videos, animations, and information about where you can go to watch the impact. If you aren’t near an impact watching party and don’t have a 10-12 inch telescope, your best bet is to tune in to NASA-TV before 4:30 am Pacific time to watch the live coverage. On your computer, go to www.nasa.gov/ntv.

The goal of the mission is not just to create a really big explosion on the moon. The “shepherding spacecraft” will fly through the plume created by the impact and will look for signs of water ice and hydroxyl ions — the same chemical signature of water that was detected in unexpected abundance by the Chandrayaan-1 mission. (See my last post.) Unlike any previous mission, this impact is expected to excavate a crater 3 meters deep, and so it will let scientists see if there is water ice below the surface, and if so how much.

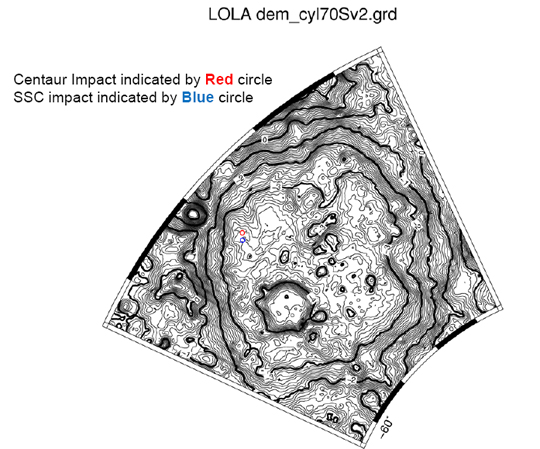

The impact site will be the crater Cabeus, near the lunar south pole. (This is a slight change from the announcement back in September – originally the target was a smaller crater called Cabeus A that is on the flank of Cabeus.) Here, from the LCROSS website, is a topographical map showing Cabeus and the expected impact sites.

Bull's Eye!

I think there are several cool things about this picture. First, note the source: LOLA, the altimeter aboard the LRO mission. One of the great things about LCROSS is the synergy between it and the other moon missions that have flown to the moon recently. Without them, the project scientists would not have such detailed information about the place they are going to. Remember, it’s a crater that is in permanent shadow — you can’t see the bottom of it from Earth!

The second thing that is impressive is the size of this crater. By comparison, the craters made by the Centaur and the shepherding satellite will be pretty puny! Note that there are two impacts scheduled. The Centaur is the rocket stage that boosted LCROSS into orbit. Instead of leaving the Centaur in Earth orbit, as they would normally do, the mission planners have taken it with them and they are using it as a projectile to create the dust plume. The shepherding satellite (SSC in the diagram) will fly through the plume and crash into the moon four minutes later. Those four minutes are the make-or-break time of the mission — that’s when the satellite will either detect water ice, or it won’t.

Also, notice that the altimeter data tell us the depth of the crater. The heavy lines are intervals of one kilometer, and the impact sites are more than 3 kilometers below what we would call “sea level” on Earth. (On the moon we call it the “geoid,” where the surface of the moon would be if it were smooth.) Fortunately, as I said above, the impact plume should rise about 10 kilometers, so there will be no problem seeing it above the rim of the crater. So Earthbound telescopes will also be able to take pictures of the plume. But the shepherding spacecraft will definitely have the best view.

Tomorrow will be an exciting day! Come back here tomorrow for pictures (I hope) and commentary from the post-impact news conference.