We come now to 1993, the middle year of my seven years in Ohio. It was a year of satisfaction and disappointment for me, and a year when storm clouds were gathering, even if I didn’t see them.

The biggest thing by far that year was that Kay and I gave up on having children via in vitro fertilization, after four expensive and emotionally exhausting failures. It was heartbreaking for her and, for me, it was one of the great failures of my life — one of those moments when life doesn’t go the way you planned and you have to just pick up the pieces and move on. The memory of our Ohio years will forever be tainted by this failure.

The storm that was brewing didn’t seem like a storm at all. I was going to come up for tenure in the spring of 1994, and everybody assured me that I had nothing to worry about. To make my prospects even better, I won an award in 1993 from the Mathematical Association of America, called the George Polya Prize, in recognition of an article I had written. At the summer meeting of the MAA, I was thrilled to be on the same stage with mathematicians who were famous and whom I looked up to. My fellow prizewinner for the Polya Prize had actually known George Polya, and he told me that Polya (who had died three years earlier) would have enjoyed my article. As thrilled as I was by all of this, I also couldn’t help thinking that this award would look great in my tenure application. With that and the support of my department, I couldn’t possibly fail.

But… the college had a poor recruiting year in 1993, and the administration announced a hiring freeze. There were lots of omens that this wasn’t the best time to come up for tenure. But I blithely ignored them.

[For anyone who doesn’t know: tenure is a tradition in American and most other European colleges and universities, whereby a professor receives a guarantee of lifetime employment. According to the rules of the American Association of University Professors, a decision on tenure must be made within seven years of being hired. The familiar phrase “publish or perish” is no joke. If you receive tenure, you have a kind of job security that hardly exists in any other profession. If you don’t receive tenure, you are normally given one lame-duck year to look for a new job. It is the most polite pink slip you can imagine, but it still means you’re fired.]

On the chess front, 1993 was my best year since moving to Ohio. For no particular reason that I can tell, I got on a hot streak in the fall and had four good tournaments in a row:

- 3-0 in an action chess tournament at the Dark Knight Chess Club in Columbus (1st place)

- 4-2 at the state championship (1st place expert)

- 4.5-0.5 at the Roosevelt Open in Dayton (tie for 1st place, and the third time in my life I had ever won an open, multi-day USCF-rated tournament. The first two were the 1988 Georgia Congress and the 1989 Roosevelt Open.)

- 3-0 in the Trick or Treat Mini-Swiss (1st place)

To be honest I wasn’t doing anything different from the previous three years, but I think I just got lucky. I played a lot of people rated below me, and I didn’t play particularly well, but they made mistakes at the right time and somehow I kept winning.

I’ll show you two games, but the first isn’t actually a game because it was the first and only “grandmaster draw” I ever played. John Dowling and I went into the last round of the Roosevelt Open tied for first place at 4-0. Here is what happened:

Dana Mackenzie — John Dowling

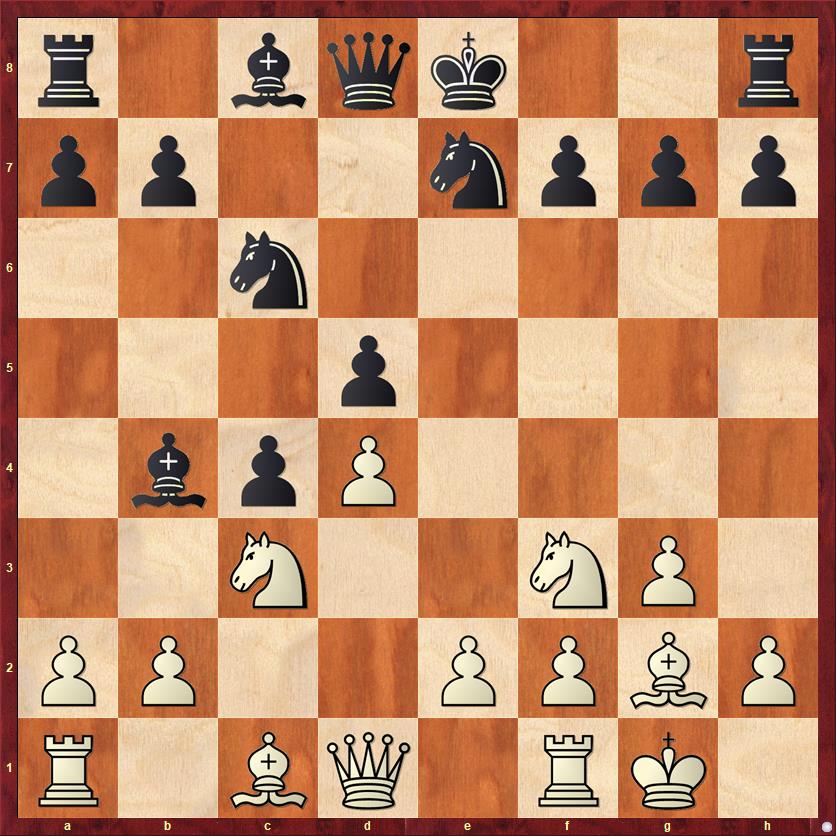

1. d4 d5 2. c4 e6 3. Nc3 c5 4. cd ed 5. Nf3 Nc6 6. g3 c4 7. Bg2 Bb4 8. O-O Nge7

FEN: r1bqk2r/pp2nppp/2n5/3p4/1bpP4/2N2NP1/PP2PPBP/R1BQ1RK1 w kq – 0 9

Here Dowling offered a draw. What should I do?

Let’s start with the position on the board. I know that this advance variation of the Tarrasch (6. … c4) exists, but I have never played against it one single time in my entire life. It’s probably considered slightly favorable for White, but it must be at least playable for Black and I’m sure that my opponent knows it much better than I do. One point in favor of a draw.

What about the money? If I play on and win, I will earn $300. If I agree to a draw now, I will probably earn $250. If I fight on and lose, I will probably get significantly less than $200, maybe even less than $100. Mathematically, it makes no sense to play on. Another point in favor of a draw.

What about sportsmanship? I have never taken a grandmaster draw in my life. Never really even thought about it. To me, like every other amateur chess player, the idea strikes me as unsporting, ethically questionable if not actually wrong. I never thought I’d take a grandmaster draw. I always thought I had more guts than that. Three points in favor of playing on.

What would my wife want? She came with me to this tournament, as she did to most of my tournaments in our Ohio years. I loved having her support. But the one thing she really didn’t like about chess tournaments was the final round. We would have to check out of the hotel before the game, and she would have nowhere to go. She could go shopping, but she couldn’t really go too far away from the tournament site or go to a movie because my game might finish. So she was a little bit of a hostage. I knew for sure that she would be thrilled if I took a draw now and we could get on the road home two or three hours earlier than we expected. Ten points in favor of taking a draw.

So, as you can see, the final calculation was not close. I accepted the draw offer. And yes, I did catch some criticism from other players who were scandalized that Dowling and I didn’t fight to the death for first place and told me that they would never do such a thing. To which I can only say, “Wait until you’re in that situation. Then we’ll see what you do.”

I know that the readers of this blog would be scandalized if that was the only game I showed you in this post! Fortunately, I have a much better game to show you, which is in some ways the flip side of the Dowling game. This was against John Stopa, a master rated about 2270, in the first tournament in my short run of success. Once again, I found myself playing an opening variation for the first time that my opponent surely knew better than me.

Nevertheless, my opponent made a couple tiny, seemingly innocuous mistakes and somehow his position completely fell apart. I wrote in my diary that it was a very “pure” game, and I still think so. It’s another example of one of my favorite themes, a mating attack in a position without queens.

Dana Mackenzie — John Stopa, 8/4/93

Action chess (game/30 time control)

1. d4 d5 2. c4 c6 3. Nf3 Nf6 4. Nc3 e6 5. Bg5 dc

Just like in the Dowling game, here we are in an opening variation that I knew existed, but had never played against. My previous games in the Slav Defense had always gone 4. … dc.

However, my head was in a completely different space compared to the Dowling game. I was playing in this tournament just for practice, as a warmup for the state championship. There was nothing at stake, and I welcomed the chance to “get my feet wet” in a theoretically important opening variation.

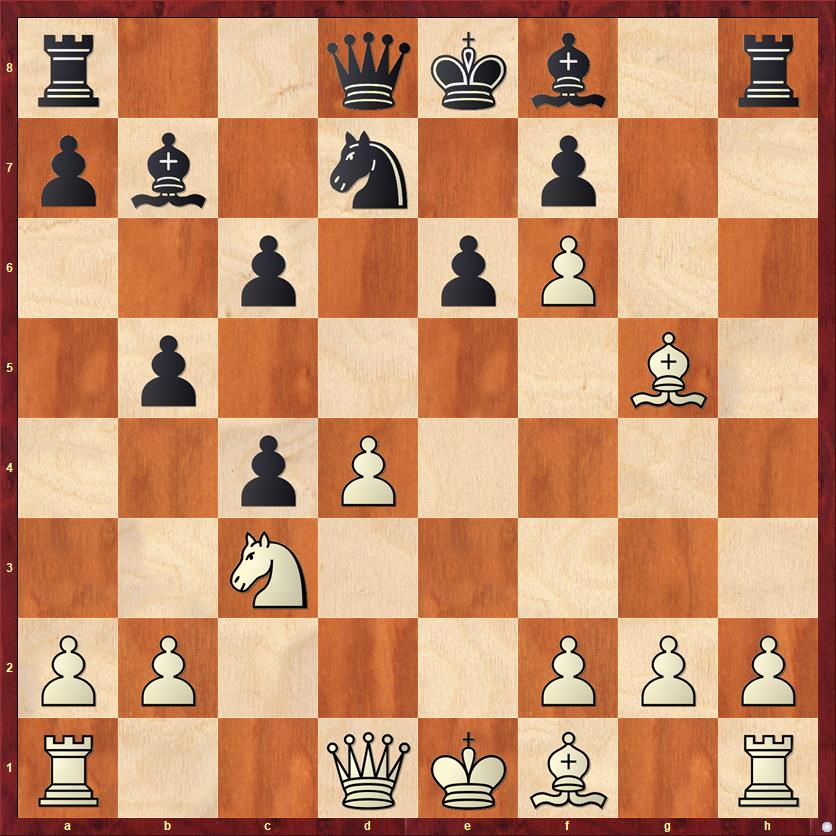

6. e4 b5 7. e5 h6 8. Bh4 g5 9. Nxg5 hg 10. Bxg5 Nbd7 11. ef Bb7

FEN: r2qkb1r/pb1n1p2/2p1pP2/1p4B1/2pP4/2N5/PP3PPP/R2QKB1R w KQkq – 0 12

This is a completely normal, book position in the Botvinnik Variation, played thousands of times. However, this was the end of my book knowledge, and from here on I was on my own. The standard move here is 12. g3, but I think that my move is not really worse.

12. Be2 …

Sometimes ignorance is a good thing! Stopa presumably knew all about this opening and knew that my move wasn’t the usual one. So he made an incorrect move to try to punish my “mistake.”

12. … b4?

Black’s normal plan in this opening is to play 12. … Qb6 and 13. … O-O-O, putting heavy pressure on the d-pawn. There is no reason that he should depart from that plan here. However, he is seduced by the possibility of winning my g-pawn and causing my kingside to collapse.

13. Ne4 c5 14. Nxc5 Nxc5 15. dc Qxd1?!

Also an inaccuracy, as we will see; he should play 15. … Bxc5 and let White be the one to decide on the queen trade. But I think it’s quite remarkable that after two moves that don’t look particularly bad (12. … b4 and 15. … Qxd1), Black is apparently lost.

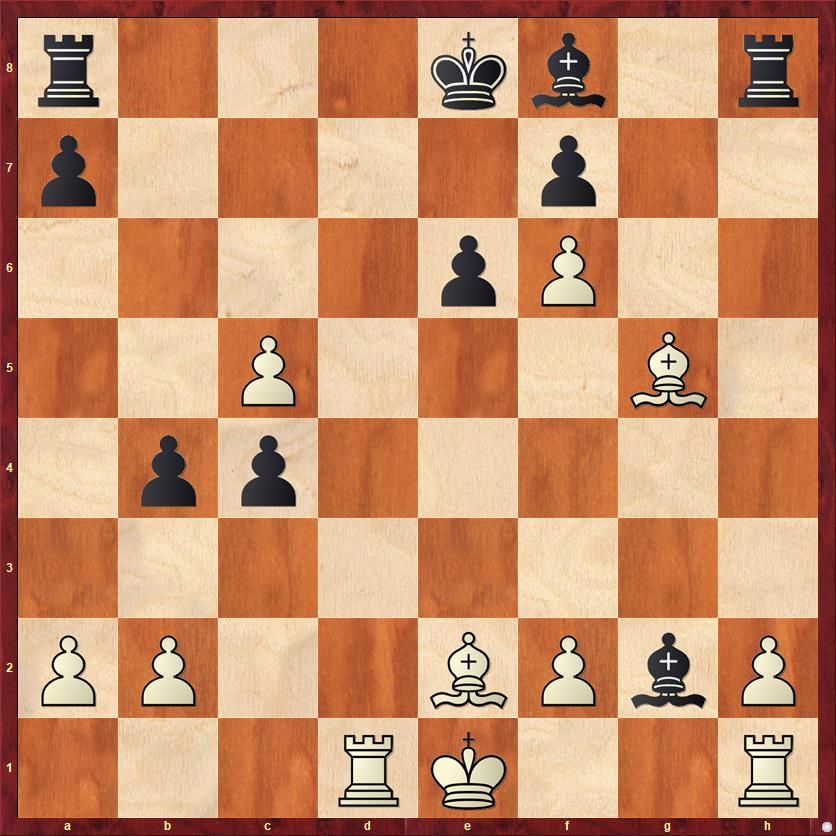

16. Rxd1 Bxg2

This is the whole point of Black’s play so far; he’s trying to “punish” me for leaving this pawn undefended.

FEN: r3kb1r/p4p2/4pP2/2P3B1/1pp5/8/PP2BPbP/3RK2R w Kkq – 0 17

Now comes the surprise.

17. Bxc4! …

Stopa must have missed this shot. (Keep in mind that we’re playing at a fast time control, game in 30 minutes.) This move completely turns the game around. Of course, Black can’t take the rook because of 17. … Bxh1 18. Bb5+ and mate next move. His next move creates some air for his king but not much, and in fact his king continues to be subject to mate threats for the rest of the game.

17. … Bxc5 18. Bb5+ Kf8 19. Rg1 Rxh2

The computer prefers 19. … Bf3, but after 20. Rd3 Be4 21. Rdg3 Bg6 22. h4 (computer analysis) White has a solid extra passed pawn.

20. Bf4 Rh1?

A very natural move, after which Black is now lost for sure. His only hope was 20. … Rh4 21. Rxg2 Rxf4, but after 22. Rh2! Black is still scrambling to survive. His king position is unbelievably awkward.

FEN: r4k2/p4p2/4pP2/1Bb5/1p3B2/8/PP3Pb1/3RK1Rr w – – 0 21

I’ll give you a little space in case you want to look for White’s winning move. Here it comes:

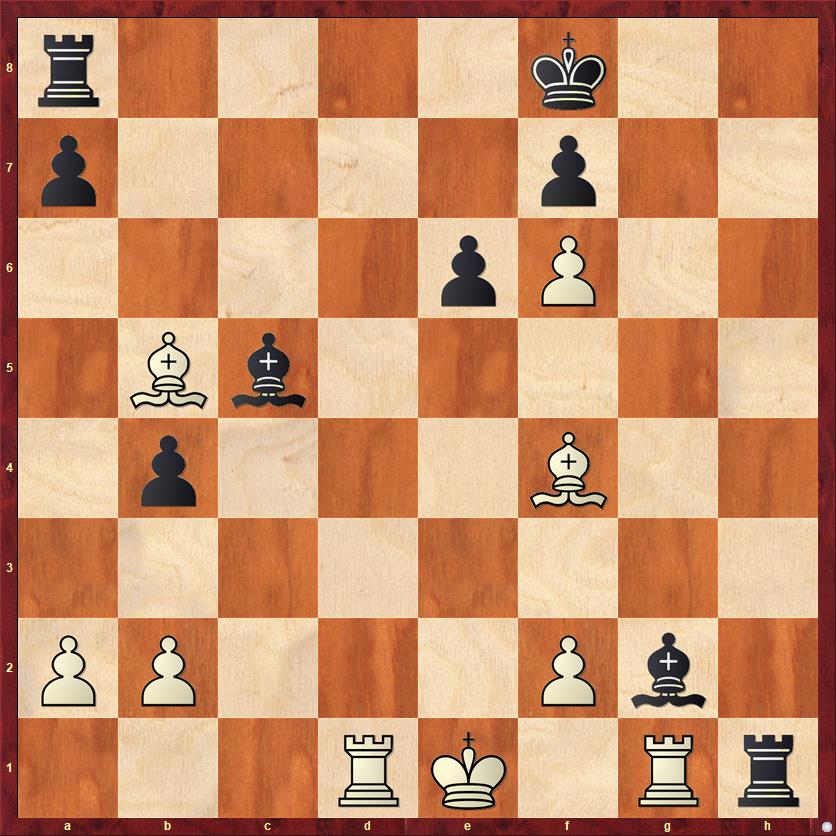

21. Ke2! …

Isn’t this exquisite? I always love it when the king makes the game-winning move. The point, of course, is that Black can’t trade rooks because 21. … Rxg1 22. Rxg1 B-any 23. Bh6+ is mate. This must have shocked my opponent as much as the mate that I threatened with my 17th move. You don’t see such a thing very often, a mate with two bishops and a rook on a wide-open board. Of course it’s really the f6 pawn that is the hero in this game, even without moving.

He tries to salvage the position by playing the move he should have played on move 20, but the tempo lost is crucial: I’m now just completely winning.

21. … Rh4 22. Rxg2 Rxf4 23. R1g1 …

Threatening mate again.

23. … Rxf2+ 24. Rxf2 Bxf2 25. Kxf2 Rd8 26. Rc1 …

Keeping Black’s rook tied down to the back rank.

26. … Kg8 27. Ke3 Kh7 28. Bd3+ Kh6 29. Rc7 Rf8 30. Kf4 Rd8 31. Be4 resigns

It seems as if Black’s king has been in a mating net constantly from move 17 on, and he is running out of ways to escape.

Lessons:

- Think twice before you say, “I would never…” You might have to eat those words someday.

- Sometimes it’s to your advantage to not know the theory of an opening! Just play the moves that make sense to you. Eventually you’ll probably play a move that isn’t “book,” but your opponent might overthink and overreact to this non-book move.

- I like to call a pawn on the sixth rank, like the f6 pawn in this game, a “bone in the throat” pawn. If you can maintain it there for a long time, it very often chokes the opponent’s king.

{ 2 comments… read them below or add one }

Great game, Dana. As a Buddhist, we’re convinced that being judgmental is rarely skillful. No one should blame you for taking a GM draw. Sometimes, many times, spending 1 hour with a loved one is worth 100, or 1 thousand bucks!

This game bears ever so slight resemblance with the “greatest opening novelty of all times”, Polugaevsky – Torre, Moscow, 1981.