All of the eyes in the chess world are on London this morning, as the second-to-last round of the 2013 Candidates Tournament is under way. As most of you probably know already, the unbelievable happened in round 12.

First, Vladimir Kramnik stunned Levon Aronian, who until just a couple days ago had been tied for first, in a game that chessdom.com rather uncharitably called a “blunderfest.” (That’s easy for a commentator sitting at a computer to say. Just try playing a game with so much at stake.)

Then Magnus Carlsen, who previously had been unflappable in inferior positions, cracked and lost against Ivanchuk, who had been in seventh place. The unbelievable turnaround puts Kramnik in first place with two rounds to play.

But that’s all I’m going to say about the Candidates Tournament today, because along with 166 other people I’m playing in a tournament in Reno, the 2013 Larry Evans Memorial. By the way, that’s twenty more players than last year. The Open section is bigger than I’ve ever seen it before, with about 60 players. Tournament director Jerry Weikel decided to combine the Open and Expert sections, because in the past there weren’t enough experts to justify a separate section. He may go back to having an separate Expert section next year.

In effect, though, I have been playing an Expert schedule this year. That’s because I have not played well enough to get paired against any masters. My score is 2-2, with one win, one loss, and two draws. I expect that I will be paired against an expert or A player again this round, and even if I win that game there’s still a pretty good chance that I will be paired down in the last round. I’m disappointed both in my result so far and the fact that I may not get to play any masters. The chance to play against masters is one of the big reasons I like to come to the Reno tournaments.

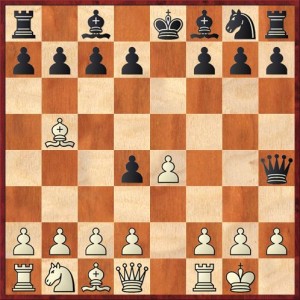

This year, however, there was one other reason that I especially wanted to play in this tournament: I had a new opening variation to test out. And in round three, I got my chance. I was playing Black against Yuan Wang, an expert whom I met at Mike Splane’s most recent chess party. The game began 1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nd4 — the Bird Variation, which you all know I am a fan of — 4. Nxd4 ed 5. O-O and now I trotted out my novelty: 5. … Qh4!?

If you have read my “Bird by Bird” series, you know that I usually play 5. … g6 in this position, which I call the Blackburne Variation (or Subvariation). However, a month or so ago I got an interesting e-mail from a Swedish player named Gustav Fhager, who strongly advocated this new move and sent me a bunch of analysis. Then this week, Gustav (believe it or not) flew all the way from Sweden to visit me and go over his opening. That is truly somebody who is passionate about his openings!

Gustav has asked me not to reveal much of his analysis yet and so I won’t. However, let me just say that this move is not as outlandish as it may appear at first glance. It’s actually very logical: having tempted White to trade knights, Black now exploits its absence to target White’s castled king. The continuation that I expected was 6. d3, and in fact that is what Yuan played. Now came the second part of Gustav’s two-part novelty: 6. … Bd6!

This move looks just as crazy as the last, but I think it is essential to justify the early queen sally. White does not have enough time to bring his queenside pieces to the aid of his king, and therefore he is forced to play a weakening pawn move: either 7. h3, 7. g3, or 7. f4. Gustav’s reams of analysis shows that Black gets a reasonable game in call cases. Yuan chose 7. g3. I got a close to equal game out of the opening, I think, and then Yuan made a mistake on move 34 that allowed me to sac the exchange and get to a completely winning endgame.

Unfortunately, I botched the endgame and had to settle for a draw, which cost me the opportunity to christen the Fhager Variation with a victory. Grrr!

At least I got the “karma point” back in round four. In that game I botched the opening, and instead of defending a wretched position I decided to play an unsound piece sacrifice instead. And it worked! My opponent played a lot of indecisive moves and I ended up saving a half-point from a game that I had no business surviving.

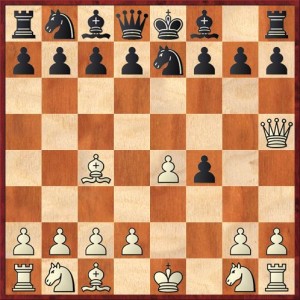

My only win so far came in round two, and you’ll be amused when you see the opening. I was White (my only game as White so far), and the game started 1. e4 e5 2. f4 ef 3. Bc4 Ne7 (a move I’ve never seen before) 4. Qh5!?

By this point you must be wondering if I missed the lesson about not bringing out your queen too early. But once again, why not? Black has misplaced his knight, and now 4. … Ng6 is forced, which allows White’s queen to remain secure on h5. It does some useful things on that square, controlling the d5 point, plus Black can never really rest easy with the queen and bishop still lined up against his king. It also prevents him Black from defending his f-pawn with … g5, which may have been one of the ideas behind 3. … Ne7.

Anyway, I ended up winning back my gambit pawn rather easily, but perhaps too easily — the middlegame, I thought, was about even. But then my opponent played too aggressively, created some weak pawns that were easy targets for my pieces, and despite some adventures in the endgame I managed to bring the point home.

Two more games today. I’ll post a final report, along with winners, later tonight.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

Thanks for the mention.

I had a question about Gustav’s idea in the Bird’s variation. I know you don’t want to discuss it online so I sent you an email.

BTW, I found a handful of games in the chess.com database with 5… Qh4 but none with 6 … Bd6.

Dana, I wanted to mention that even though Qh4 looks very playable, my own feel is that White retains a lasting space advantage out of the opening. I suppose the only interesting question is how large.

I think that the way you handled it was very good, not really trying to do anything special but just getting all the pieces out. Eventually Black is going to pay some kind of price for the curious development of the bishop and queen. The main question I have is whether my move 8. … Nh6 was right or whether I should have played 8. … h5 first. After 8. … Nh6 9. Bxh6 Qxh6, I didn’t have any threats any more and you were able to just get a solid space advantage. 8. … h5 would be a little bit more threatening but it makes my development even slower.

All in all, I don’t think 5. … Qh4 is a magic bullet but I think it is worth studying (and playing) some more.

I’ve been thinking through the part you are considering. I really didn’t like giving up the Bishop for the Knight. Perhaps it’s worthwhile for White to try to make it work with both queen side pieces. It’s a challenge to find squares for them, but perhaps f4 is not required. That should be interesting enough for another half dozen games!

In the game we played, I felt it was ok to trade, avoid a space issue in my camp, and try to capitalize on the influence of the e4 and f4 pawns. But thinking a bit deeper, having more pieces on the board may not be a bad thing. The h6 Knight may become a problem, as well. It’s not well placed on f6 due to White’s pawns, and if Black has to play something like f6 to make space for it, then it doesn’t sound good.

On h5, I think it’s definitely a valid idea. I think perhaps Black may wish to consider a bit of creativity for King safety, as neither the king side nor the queen side will look very good then. In particular, I played Qe2 instead of f4 in the game to keep it flexible. h5 may be a bit committal before White has played f4.

In addition, just looking at the strategy for the long term, I think it’s an interesting challenge for White to figure out a way to castle queen side. The obvious problem is the queen side development, so Na3 may be considered. This has the benefit of trying to roll Black off the board on the king side.

Overall, I’d like to try to find a good way for White to handle the development issues for both sides. It should provide interesting material for some blitz games!